Novelist John Larison Hears “The Story of The Person, not The Story of The Labels”

John Larison’s WHISKEY WHEN WE’RE DRY, published last week by Viking, is a gritty and lyrical American epic about a young woman who disguises herself as a boy and heads West. In the spring of 1885, seventeen-year-old Jessilyn Harney finds herself orphaned and alone on her family’s homestead. Desperate to fend off starvation and predatory neighbors, she cuts off her hair, binds her chest, saddles her beloved mare, and sets off across the mountains to find her outlaw brother Noah and bring him home. Told in Jess’s wholly original and unforgettable voice, the book draws readers into its expansive adventures that tangle with the myths that are entwined with our history.

John Larison’s WHISKEY WHEN WE’RE DRY, published last week by Viking, is a gritty and lyrical American epic about a young woman who disguises herself as a boy and heads West. In the spring of 1885, seventeen-year-old Jessilyn Harney finds herself orphaned and alone on her family’s homestead. Desperate to fend off starvation and predatory neighbors, she cuts off her hair, binds her chest, saddles her beloved mare, and sets off across the mountains to find her outlaw brother Noah and bring him home. Told in Jess’s wholly original and unforgettable voice, the book draws readers into its expansive adventures that tangle with the myths that are entwined with our history.

In this “Meet Our Author” interview, John Larison reveals what inspired him to write WHISKEY WHEN WE’RE DRY, how his version of “The West” differs from prior creative renderings, and his feelings about adopting the voice of a complex character whose identity and background are so different from his own.

What were the origins of your book?

Novels for me begin like rivers, tiny springs that eventually converge into torrents that cannot be stopped.

Novels for me begin like rivers, tiny springs that eventually converge into torrents that cannot be stopped.

As a boy, I spent a formative spring, summer, and autumn living on and off Oregon’s Hart Mountain Wildlife Refuge, where my parents were working with cattle ranchers. At events like July 4th or Roundup, my brother and I found ourselves half-adopted into the ranching families, and suddenly we had no shortage of cousin and uncle-types eager to teach us the cowboy arts, like roping, shooting, spatting tobacco, and the kid version of bull riding, which is climbing atop a poor sheep who only wants to run away. Those experiences—and our time on the high desert, where cranes and antelope and bighorn sheep wander under painted skies—no doubt are the headwater spring of WHISKEY.

Any fiction I write has part of its origin in other writing. Living at the end of the Oregon Trail, I’ve long been fascinated by the early accounts of pioneers; luckily many of those letters are anthologized at local public libraries. As a writer, I became increasingly interested in the patterns of language I found in those letters early settlers were sending to their relatives “back east.” The best of these letters offer a singularly American music of sorrow, gratitude, mourning, and hope. That music was playing on repeat in the back of my mind as I wrote WHISKEY.

Ultimately, a hundred little springs of inspiration converged into a river on a single night. It was in December, and I remember the rain, which was turning to heavy snow. I was alone walking the streets near our home; I was trying to work through a problem in the novel I’d been writing for several years about the survivors of a school shooting. I was listening to a Gillian Welch album, and then the song “Ruination Day” began. In its rhythm, I heard a horse trotting. I let myself drift away from the problem at hand, and when the song ended, in the silence, I heard an old woman’s voice. Her words remain the first lines of the novel.

How would you say WHISKEY differs from other works—novels or movies, contemporary or otherwise—about the West?

For a novelist, the American West offers a gold mine of tensions, both internal and external. It presents a diverse cast of characters who face high stakes and steep odds. And it provides the chance for wide-open fun; who doesn’t like a little horse race through the canyon lands? Maybe more to the point, novels about this formative time possess a unique power to speak to the hopes, sorrows, and misgivings of those of us who live and die in a nation of immigrants.

I guess I believe our culture needs—urgently, desperately—new Westerns that are not black-and-white but rather are as spectacularly gray as our national reality.

In WHISKEY, I sought to write an epic about the West for all Americans, one that doesn’t flinch from the historical truth, yet still retains the magic of fast horses and summer love—a novel that might read like a new national origin story. My hope is that the book confronts the myths of our identity while also celebrating those aspects of the American character that are too often obscured by divisive and simplistic retellings of our past.

Your narrative is written in the voice of Jessilyn Harney, a woman born into a biracial family in the 1860s. What were your feelings about telling the story of someone whose identity and background are so different from your own?

Undertaking any novel is a heady responsibility, one that the writer—I believe—has an ethical requirement to approach with earnest, authentic effort. Jesse had entrusted me with her story, or at least that’s how it felt at the time. I did feel overwhelmed by the enormity of all I had to learn if I was to give Jesse her due, but each day I trusted the art—and its process—to guide us both through the wilderness.

You say that Jessilyn is a woman; I’m not sure Jesse (the name she gives herself later in the novel) would use that label if she was here with us today. For much of the novel, she presents herself as a man, so you might be inclined to ask if she is a depiction of someone who today might identify as trans. If you asked Jesse that question, I bet she would shrug and say, “I’m just me.”

You say that Jessilyn is a woman; I’m not sure Jesse (the name she gives herself later in the novel) would use that label if she was here with us today. For much of the novel, she presents herself as a man, so you might be inclined to ask if she is a depiction of someone who today might identify as trans. If you asked Jesse that question, I bet she would shrug and say, “I’m just me.”

But definitely the people around Jesse in 1885 categorize “her” in specific ways. At the start of the novel, those categories are used against her. She isn’t allowed to do certain things or think certain thoughts because people see her as female and Mexican or Native American. In the middle of the novel, she uses those categories against the people who would oppress her by hiding herself behind white-male clothing, mannerisms, and patterns of thought. Late in the novel, she transcends these labels all together to become something that is purely Jesse Harney—and that is the human being telling our story.

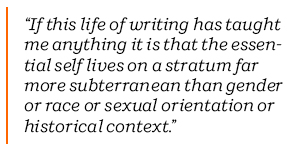

If this life of writing has taught me anything it is that the essential self lives on a stratum far more subterranean than gender or race or sexual orientation or historical context. An honest novelist—like an honest friend, I think—must hear the story of the person, not the story of the labels.